With ports closed because of the war, vast amounts of wheat can’t reach nations that rely on it

PERVOMAISK, Ukraine — The grain Ukraine produces is found everywhere. Much of the bread in the Middle East is made from it. Much of what aid organizations distribute to stave off famine in Yemen is made from it. Much of what feeds Chinese livestock that in turn feeds people worldwide is made from it.

Even with a calamitous war about to enter its seventh week, Ukraine is on track to harvest most of its vast grain fields this summer — though there are mounting concerns that war-related supply shortages may reduce output by as much as a third. The country has 30 million tons of wheat in storage, too.

“Last year was a record wheat-producing year for the whole country,” said Dmytro Grushetskyi, an industrial farmer with nearly 30,000 acres of cropland near the central city of Uman who also runs an agricultural data company that monitors harvests in Ukraine, Russia and neighboring countries. “Ukraine is actually full of grain. Our stocks are full.”

“But now we can’t get the grain out,” he said, putting his finger on the problem that may lead to an enormous spike in grain prices and exacerbate hunger around the world, “which means Ukrainian farmers, and the rest of the world, are screwed.”

.webp)

A Soviet-era grain storage warehouse outside Uman. A lack of storage space has farmers using old, dilapidated storehouses. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

All of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports are closed off to the world by a Russian blockade that includes floating mines. A battleship the Ukrainian navy scuttled to avoid capture is blocking access to grain stores at the country’s biggest port in Odessa. And after 20 years of investment in farm-to-port infrastructure, wheat exported by train is just a tiny fraction of what is exported by sea.

Without export income, Ukraine’s giant industrial agriculture economy is grinding to a halt, threatening bankruptcy for farmers and increasing the likelihood that the global grain market — and other food supplies that depend on it — will see increasingly worse scarcity even in the unlikely event that the conflict ends soon.

David Beasley, executive director of the U.N. World Food Program (WFP), told the U.N. Security Council that food prices are already skyrocketing. A third of the world population relies on wheat as a dietary staple. Anger over rising food prices has always been a major underlying cause of civil unrest the world over.

The war’s knock-on effects on energy and fertilizer supplies are already rippling through agricultural supply chains, raising prices of basic goods for nearly everyone on the planet.

Countries such as Egypt — the biggest importer of Ukrainian wheat last year — as well as Lebanon, Pakistan and others, get most of their wheat from Ukraine. The country produces about a fifth of the world’s high-grade wheat and 7 percent of all wheat. The WFP buys half of its grain from Ukraine.

Grushetskyi has more than $2 million worth of wheat trapped in storage, and like other farmers across the country, he worried that without being able to sell any of it, he won’t be able to pay workers, buy seed, fuel and fertilizer, maintain equipment or pay outstanding bills, putting the future of his company in peril.

.webp)

Dmytro Grushetskyi in a grain storage warehouse outside Uman. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

A trader he works with at the Odessa port, Oleksandr Chumak, laid out the industry’s despondency in plain terms.

“There is nothing else to do but give the grain away to the army or as humanitarian aid. Ukraine, thankfully, will not starve,” he said. “But if we are talking about global food security, well, that is already a fragile system. Climate change, supply chain chaos, and now this war — in six months’ time, poor people will starve to death. I don’t think the world understands that yet. For their own sakes, movement of food through the Black Sea must be negotiated.”

For Ukrainian farmers, however, there are more-immediate problems.

It took just two hours on the first morning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine for its forces to occupy the 55 square miles of Volodymyr Khvostov’s industrial-scale farms, which raise wheat, rapeseed, sunflowers and dairy animals in the country’s highest-yielding region, between the Crimean peninsula and the southern city of Kherson.

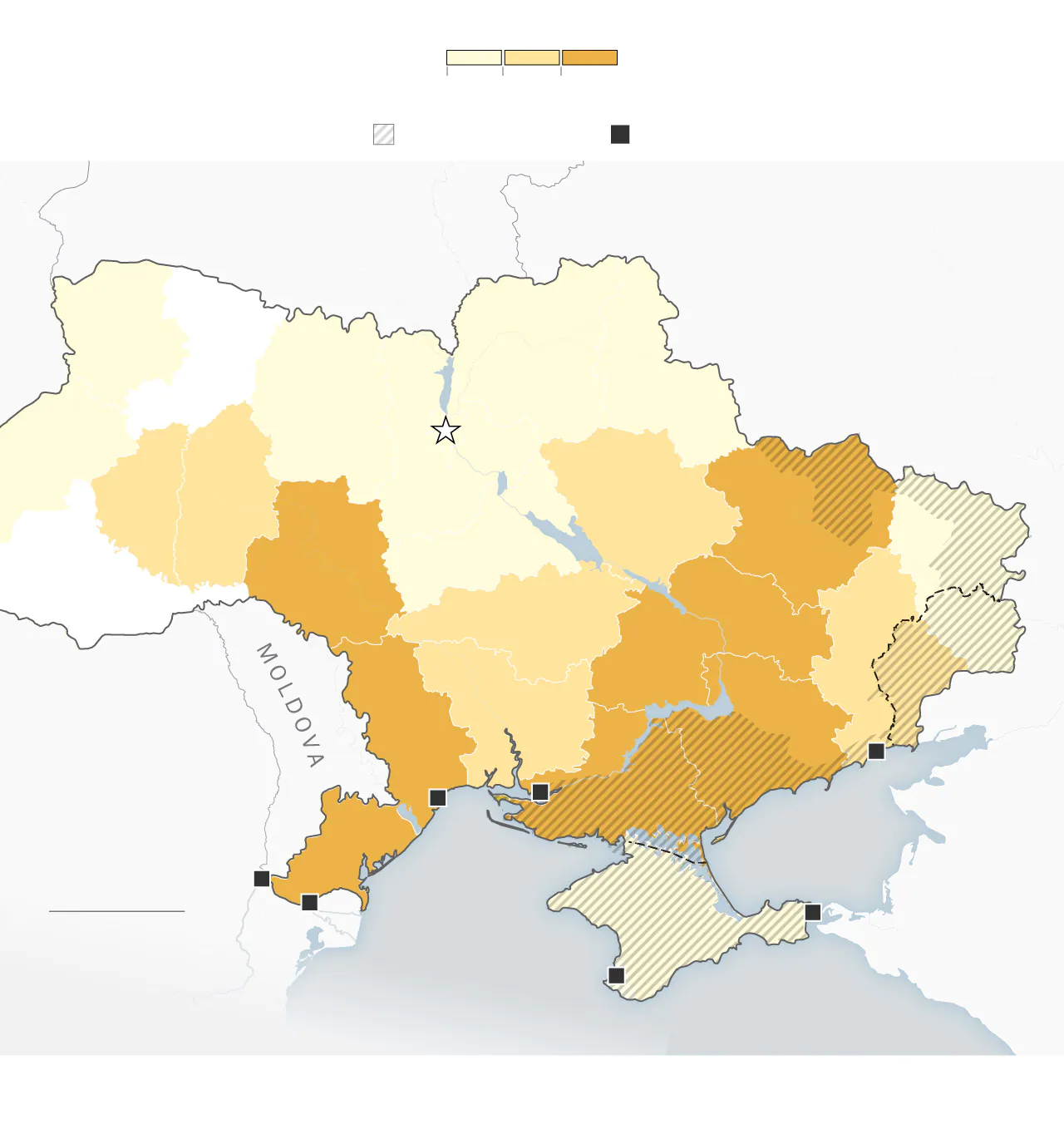

Since the war began, Ukraine’s most productive agricultural regions have come under Russian control.

Sources: Institute for the Study of War, U.S. Department of Agriculture (JÚLIA LEDUR/THE WASHINGTON POST)

Key canals that irrigate millions of acres have been damaged in fighting.

The diesel that fuels tractors and other equipment is increasingly unavailable across the country, either because it was once obtained from Russia or because Russia has bombed local fuel storage sites.

Key moments in the agricultural calendar — fertilizing, tilling and, soon, planting — are passing while farmers struggle to source essential supplies, and while others have left to go fight. Farm employees are exempt from conscription, but many have joined out of a sense of duty.

“We are still planning to harvest, even if it will be difficult,” Khvostov said. “But if we don’t defeat the Russians by then, it won’t matter to the rest of the world.”

.webp)

A man carries firewood to a hut outside Uman that serves as a seasonal bunkhouse for farmworkers. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

Agricultural officials in Ukraine expressed worry that while their country’s army seems to be holding Russia’s army back from achieving its most ambitious goals, Russia might win in a long war against Ukraine by crippling its agricultural economy.

A collapse of industrial farming would be disastrous for Ukraine in just about every way imaginable. And because Russia is also one of the world’s biggest grain producers, it stands to gain exactly where Ukraine loses.

“It’s a secret weapon in the war,” said Andrii Dykun, chairman of the Ukrainian Agri Council. “Make Ukraine go bankrupt. Make the world buy from Russia. Of course the world will buy from them rather than starve.”

Russia has already slashed its wheat prices to make its product more attractive on the global market, though it has also threatened to limit agricultural exports to countries it considers hostile to its invasion of Ukraine. Russian food exports have not yet come under Western sanctions, and some of the United States’ largest agribusinesses, including Cargill, continue to operate in Russia.

A market area in Uman on March 25. (Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post)

“American and German companies are still operating in Russia, so while the U.S. sanctions Russia, they are financing them at the same time,” Dykun said. “The West will make us die slowly this way.”

Because agriculture is so integral to Ukraine’s economy, farmers have been lionized by their fellow citizens, their role seen almost as essential as soldiers’. And many farmers have seen it as their duty to harvest as much grain as possible, not just for their country’s sake but for the world’s.

“It’s a half joke, but maybe the West should give us armored tractors,” said Bogdan Lukiyanchuk, a farmer, agronomist and host of Growex, a YouTube channel for Ukrainian farmers.

At a gathering at his home on the outskirts of Pervomaisk — north of the city of Mykolaiv, which has come under intense Russian shelling in recent weeks — Lukiyanchuk posed for a photo with an automatic rifle.

“I sleep with one. I take another out into the fields with me just in case,” he said. “We have to keep as much of our land under our control as possible. This fight is not just for Ukraine but for everyone.”

Serhiy Morgunov contributed to this report.

Tuesday, 12 April 2022